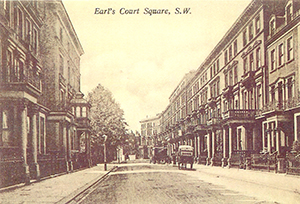

HISTORY OF EARL’S COURT SQUARE CONSERVATION AREA

EARL’S COURT SQUARE is built on land originally occupied by Rich Lodge and its extensive grounds, which were cultivated, like most of the area, as a market garden. The origins of this fairly small and modest building are unknown. Rich is one of the family names of the Earls of Warwick and Holland (another is de Vere); their estate was inherited in the early 1800s by William Edwardes, first Baron Kensington, and was known thereafter as the Edwardes Estate.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT

The first recorded development in the conservation area was a row of 10 houses called Rich Terrace constructed in 1830 on the north side of Old Brompton Road (the stretch west of Earl’s Court Road was then named Richmond Road). The Mansions and Richmond Mansions now stand on the site of those 10 houses. Further houses were added to the terrace in 1850-3 where now stands Redcliffe Close. The parallel terrace, built 1866-8, on the south side of Old Brompton (Richmond) Road, still stands. Three small houses, demolished when the south side of the Square was developed, were built behind Rich Terrace and fronting onto Rich Lane, which still exists as a service road between the south side of the Square and the mansion blocks on Old Brompton Road

ST. MATTHIAS’ CHURCH

The earliest development (although strictly speaking is not in the conservation area) to survive into the 20th century was the High Anglican Church of St. Matthias in Warwick Road, built in 1869-72. Two schools, infant and primary, were erected to the south of it in 1873 but proved too small and were replaced by one larger school in 1898-9. A new wing was added to the southern flank of the school in 1977. The church was damaged by incendiary bombs in the Second World War and never reopened. It was demolished in 1958 and made space for the school caretaker’s bungalow and garden, built in 1962. There were three terrace houses on the south corner of the site facing onto Warwick Road, no clear record of which now exists, although they are on the map of 1879. People who remember them say they were of the same style as the houses opposite, which leads to the assumption that they were the first phase of a terrace, probably planned to run from Old Brompton Road, which was never completed. A bomb in the Second World War demolished these houses.

THE NORTH, EAST AND WEST TERRACES

The first building of the Square was the construction of No. 1, which was known as Earl’s Court Lodge*, built in 1873-5 by a builder/property developer, Edward Francis, in conjunction with nos. 280-288 and 292-302 Earl’s Court Road.

*Earl’s Court Lodge, no. 1 Earl’s Court Square, is not to be confused with the much larger Earl’s Court Lodge which had previously stood opposite on the east side of Earl’s Court Road, or with Earl’s Court House, an imposing mansion occupying what is now Barkston Gardens, or Earl’s Court (Farm) House, sited in the area to the south of the present station, or Earl’s Court Manor, sited to the north of the station, where the Manorial Courts of the Earls and subsequent Lords of the Manor had been held (the last recorded in 1856) and from which the district acquired its name.

In the same period Edward Francis commenced building the two rows of houses, which are now nos. 3-11 and 2-10 on the North-East arm of the Square,** along a road on the north side of the grounds of Rich Lodge, which was intended to be an extension of Kempsford Gardens (this road was then also called Kempsford Gardens).

The drainage was also laid for a new road, which was to be called Farnell Road, running off ‘Kempsford Gardens’ to the north, to join Rich Lane to the south: this is why the houses on the east side of the Square all have their drains running into a sewer at the back, not the front as is usual.

The mews for Farnell Road (Farnell Mews) was built but the houses, which were planned to line the road, were never started. Instead, there was a complete change of plan. Sir William Palliser, the first occupant of Earl’s Court Lodge (1 Earl’s Court Square), together with Edward Francis, conceived the idea for a far grander design: the creation of Earl’s Court Square. Sir William provided a considerable amount of finance for the scheme and the east side of the Square was commenced in 1875, followed by the west side in 1876. Nos 25-37 followed and the whole of the north side was under way by 1878. The building leases were granted to Edward Francis and Sir William Palliser by Lord Kensington and no. 12, which was of a particularly grand design and interior finish, was earmarked as a residence for one of Lord Kensington’s close female relatives; it still retains a conservatory on its porch. The south side of the Square was left open giving a view down to the river from the top floors of the houses. The houses were numbered incorporating Earl’s Court Lodge as no. 1, allowing for even numbers to be continued later on the south side.

**It is to be noted that an 1879 map of the area, which is much copied, is inaccurate in this and several other respects. It conflicts with building records, which are almost certainly more accurate.

STYLE & USEAGE

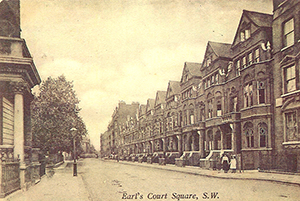

The north, East and west sides of the Square are in the late Italianate style, with Corinthian porticos and bath stone features that were initially unpainted. The Square became gradually gloomier and gloomier as the stone became blackened in the smoky London air until after the First World War when nos. 15, 17 and 19 were painted white, to be followed by others until all were finally painted after the Second World War. All the houses were large and no cost was spared in the quality of the building work or materials used. The architect incorporated metal girders, an innovation in the construction of domestic architecture. The master joiner in charge of the work, however, did not trust in the durability of iron, which he suspected might rust or crack, as against the proven qualities of wood and the main girders supporting the floors above the large front bays have companion wood beams installed alongside the metal ones. Superior lead damp courses under the footings of the main walls have withstood movement.

The development was intended to provide family houses for the expanding wealthy classes who could afford a retinue of servants housed on the top floors. The extra servants’ floor on nos. 25-37 may or may not have been added after the houses were completed. The 1891 census shows that in those houses, which were in single-family ownership, the households were large, with servants considerably outnumbering the owning family. The houses on the north side vary in width but not in depth.

It is known that some houses were bought ‘off plan’ with features and alterations added by the prospective owners. Some houses had the newfangled electric light installed whilst others relied on the standard gas ‘carcasses’ for lighting. The latest and most sophisticated kitchen ranges were installed, handsome pieces with back boilers to supply constant hot bath water. No. 15 had an extension to the rear ground floor to accommodate a billiard table for a rich young banker and his bride and the salon, or ‘ballroom’, was decorated with gold leaf finish on the Italian plasterwork. Some houses were furnished with fireplaces in all the servants’ rooms and even in the sculleries, and with bathrooms and flush lavatories at top and bottom of the house, to make the lives of the household staff as tolerable as possible. Other prospective owners skimped on such amenities for servants, or perhaps the houses were completed with the minimum before buyers were identified, because Francis and Palliser had misjudged an oversupplied market and many were not sold.

In 1879 Edward Francis went into liquidation. In 1881 28 houses were still empty, with only six of these sold by 1885 and some still on the market in 1890. In the end not many were used as family houses; most were turned into boarding houses, hotels, schools and academies or split up into rudimentary flats.

THE MANSION BLOCKS

Herbert Court Mansions were the next development, in 1891-2, followed by Langham Mansions in 1894-6, originally with a billiard room and a reading room (euphemism for smoking room) in the basement. In 1890-2 George Whitaker, the architect, was responsible for demolishing what remained of Rich Lodge together with the old Bolton Beer House on the corner of Earl’s Court Road and Old Brompton (Richmond) Road and designing a new public house known for the next hundred years as The Boltons (briefly called Whitaker’s and O’Neill’s and currently called The Bolton) together with nos. 304-322 Earl’s Court Road and The Mansions in Old Brompton Road.

Four blocks of Wetherby Mansions were built in 1892-4 on both sides of what was then called Wetherby Road West. The fifth block of Wetherby Mansions was built in 1895-7 together with Richmond Mansions, which replaced the eastern end of Rich Terrace. Part of Richmond Mansions was severely damaged by a bomb during the war. The rest of Rich Terrace remained, until it was demolished to make way for Redcliffe Close in 1936. Building in the Square was completed in 1965 with the erection of Northgate House between nos. 1 and 3 on the site of a builder's yard belonging to no. 3. Redcliffe Close was granted planning permission for a further storey in 2003.

THE SQUARE GARDEN

The Square Garden, under the control of the Edwardes Estate, although dull and somewhat dreary, was well managed with an almost full-time gardener until 1939. However, in the 2nd world war the handsome cast iron railings were taken away for scrap metal and 5 huge emergency water tanks filled the southern half of the garden. An Anderson shelter was erected in the road opposite nos. 20-28 but was only ever used as a handy WC. The water tanks were removed in 1945 but the concrete bases remained in place for several years after.

The freehold of the garden was purchased from the Edwardes Estate by a property speculator after the war. The railings were replaced by green wire netting which soon acquired gaps and the garden was rarely, if ever, tended: it became an overgrown area and a dump for broken bottles and unwanted objects which made it too dangerous for smaller children to play in, although it was sometimes used by older boys as a rough football pitch. In 1971-2 a group of residents took it in hand, a voluntary working party was formed and it began to look more like its original self. In 1975 the newly formed Residents’ Association brought the garden under the 1851 Kensington Improvement Act and a landscape gardener and resident, Christopher Fair, designed the present layout and planned tree and shrub planting. The established London Plane trees were left, however, and have now grown to dominate the square; one on the South side, was blown down in the 1989 gale, allowing in a little more sun. The 1851 Act bestowed jurisdiction over any aboveground construction in the garden area to the residents and so effectively brought to an end oft-mooted plans to build an underground car park since access to it would not be possible without their consent. A 50% share of the freehold of the garden has been purchased by the Garden Sub-Committee (which comprises the garden levy payers). New iron railings were purchased in 1977 and further improvements followed their installation: we now have a garden, which regularly wins top awards.

THE BOMB

The only bomb, which dropped in the Square proper, was in 1942. It demolished nos. 25-27, Queen’s Court, (then serviced rooms) behind the facade, which remained standing. The lower parts of the two staircases, with some of the main walls, together with the front basement rooms (where fortunately the 20 -30 occupants had taken shelter), remained intact. The round pillars to the front portico were seriously weakened and had to be replaced by ‘temporary’ square ones. The bomb blew out the majority of windows in the Square and brought down much plasterwork in adjacent houses but the original structure of the buildings was such that the damage was minimal for the size of bomb. Queen’s Court was rebuilt as flats in the late 1940s.

RECENT TIMES

Until the 1920s the area was patrolled by a Beadle, employed by the Edwardes Estate, who maintained propriety and environmental standards (shades of the present PCSOs?) and enforced conditions contained in the initial leases such as not permitting washing to be hung out either at the front or backs of houses. In the early 1970s the Edwardes Estate sold the freeholds it owned in the Square, which was still the majority, to property speculating companies owned by the brothers Kirsch. The houses in the Square were nearly all hotels, hostels or rooming houses or were poorly converted into flats; they were painted in a variety of bizarre colours. Earl’s Court Square was now extremely run down, with dilapidated buildings and a steeply rising crime rate. There were two squalid brothels, they were at no. 9 and in the A-L block of Wetherby Mansions that were eventually evicted by the borough’s Health Inspector and a sordid murder occurred at no. 4. Vietnam boat people (Asylum Seekers) were housed in nos. 2 and 4 until they were ousted, under police pressure, for supporting themselves on hard drug dealing. Nos. 51-55, which had been a nurses’ hostel, Cumberland House, were occupied by squatters; they suffered from planning blight which rendered the block virtually unsaleable because the London County Council (forerunner of the Greater London Council) had designated that side of the square for eventual demolition to make way for an expansion of St. Cuthbert’s with St. Matthias School.

It was developed into flats in 1983-4 after the planning blight was eventually lifted in 1981.

Property was cheap to buy but expensive to maintain. Many freeholds were sold to Housing Associations, which had government funds to convert them into flats as affordable housing, with subsidised maintenance, for London’s lower income working population. These developments improved the appearance of the Square considerably. Fifteen houses in the Square are now owned by Registered Social Landlords whilst the great majority of the rest have been converted into high quality flats for owner occupation, with the last vestige of ‘seediness’ gone. At the time of writing two of the large houses and three of the ‘Dutch’ houses are single-family residences.

In 1974 a property development company acquired nos. 45-47 and no. 33 with the intention of demolishing the buildings above the ground floor and developing high-density flats. This demolition was halted at second floor level by the Greater London Council, under an emergency Personal Conservation order, requested by the newly formed Earl’s Court Square Residents Association. Unfortunately, powers did not exist to force the reinstatement of the upper floors. Nos. 43-47 were sold to the Family Housing Association and developed as affordable housing. The upper windows of no. 33 were restored to their original design when Nicholson Estates redeveloped nos. 33-37 into Matiere Place as flats, which completed in 2002.

After considerable work by the Residents’ Association the Square was granted full Conservation Area status by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in 1975. One of its stipulations is that the buildings on the west, north and east sides must be painted Magnolia BS4800 08B15 with woodwork in white but the colour of front doors is at the owners' choice. The colour for the house numbers is Black, Garamond and 7" in height. The latter detail is not in the Conservation Area document but is something that ECSRA recommended.

At first the Conservation area only covered the original houses built or planned by Edward Francis and Sir William Palliser, plus Herbert Court and Langham Mansions, but it was extended in 1997 to embrace 304-326 Earl's Court Road, Wetherby Mansions and 248-252 Old Brompton Road. In 1998 266-302 Earl's Court Road, no. 1 and Northgate House Earl's Court Square, and 16-38 Warwick Road were added and all these properties were brought within the embrace of Earl’s Court Square Residents’ Association. Additionally Penywern Road was brought within the Earl’s Court Square Conservation Area in the year 2002, but has its own Residents’ Association and its history is not covered in this paper.